In his book Balkan Ghosts, a travel log and mini-history of the Balkan countries, Robert Kaplan writes: “The more obscure and unfathomable the hatred, and the smaller the national groups involved, the longer and more complex the story seemed to grow.” It captured perfectly my reaction after reading the book and learning about the histories of Serbia, Croatia, Bulgaria, Bosnia, Albania, Turkey, and various other neighbors. So much fighting over territorial, ethnic, or religious differences that appear to be so inconsequential relative to the bloodshed.

Much of the fighting has to do with perceived historical grievances. Kaplan writes:

Macedonia defines the principal illness of the Balkans: conflicting dreams of lost imperial glory. Each nation demands that its borders revert to where they were at the exact time when its own empire had reached its zenith of ancient medieval expansion.

I read the book because I was visiting Montenegro, Bosnia, and Serbia. I recently got back from the trip. Seeing the places in person, as usual, made me engage with history that I probably ought to have known but hadn’t prioritized knowing till now. Travel makes you do that. It also makes you keep up with a place in the news after you leave. 80% of The Economist used to be uninteresting to me; now, when I flip through and see one of the random articles about, say, Indonesia, I’ll read it, because I’ve been there.

Sarajevo was haunting. It’s a small and pretty city, especially the old town. And quite cheap. But to be in Sarajevo is mainly to see grave yards all around and to visit museums dedicated to a genocide that happened only 20 years ago. Normally, when you think of the horrors of history, you think of grainy black and white photos. The slaughter of Bosnian Muslims (by Orthodox Christian Serbs) happened in the era of color video and color photos. It was so recent that there are people alive right now in Sarajevo who are missing all the men in their extended family.

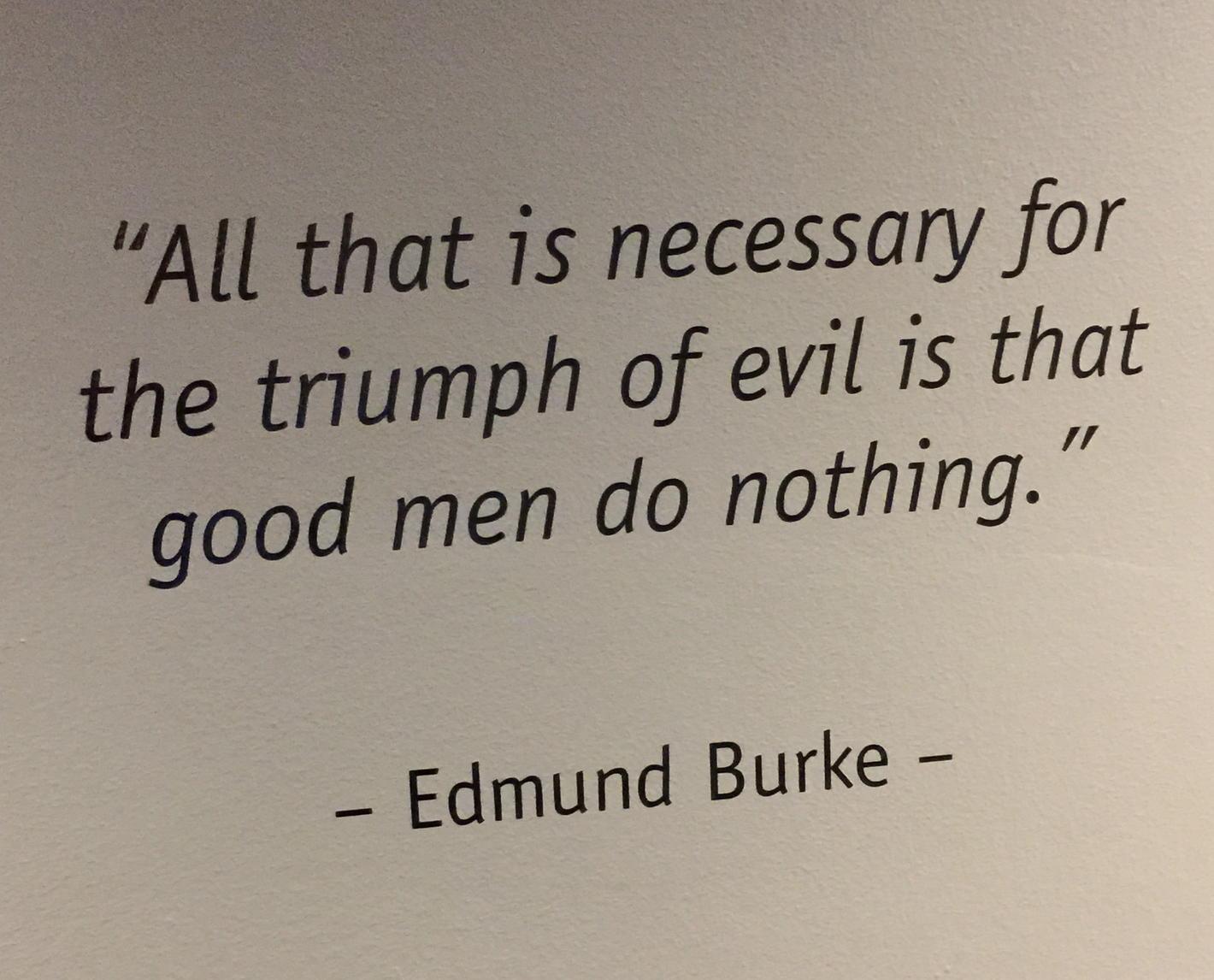

The Srebrenica massacre museum really emphasized Western negligence during the ordeal. The cowardice/incompetence of the U.N. peacekeepers was a surprisingly recurrent theme. After the U.N. declared Srebrenica a “safe city,” thousands of Muslim men gathered there, thinking they were safe. In fact, they made themselves a convenient target for the Serbian army who overpowered the hapless peacekeep ers and executed 8,000 men and boys in 48 hours. The photo embedded to the right hangs on the wall as you exit the museum. You can’t help but reflect on the costs and benefits of humanitarian interventions.

ers and executed 8,000 men and boys in 48 hours. The photo embedded to the right hangs on the wall as you exit the museum. You can’t help but reflect on the costs and benefits of humanitarian interventions.

After Sarajevo, I went to Belgrade. The Belgrade tour guide referred to the 90’s as a “terrible, sad time” where people on all sides made mistakes. He expressed remorse for the 1,000 Serbian civilians killed during the NATO air strikes. No mention of Muslims.

Neither Belgrade nor Sarajevo maintain blockbuster tourist attractions. Sarajevo is prettier; Belgrade maintains a Soviet aesthetic. The Bosnians and Serbians I met were all hospitable and intelligent. In both places I think you visit for a history trip: to learn about Tito and communism, to learn about the Balkan wars, to try to keep up with who hates who for which ethnic or religious reasons, to try to figure out the difference between Catholicism and Orthodoxy.

Here are Tyler Cowen’s impressions of Belgrade. We were there together at a conference. I, too, am very glad I made it to Serbia. And I hope there can be lasting peace in the region.

Full highlights of the Kaplan book below the fold. It’s a good book to read before a visit.

The intellectual point of view on the Balkans goes something like this: The war in Bosnia was brought about not by ethnic hatreds as much as it was by evil men, and it could have been stopped at any point along the way. Indeed, Muslims and Christians in Sarajevo have a long history of peaceful communal relations. There were Serbs fighting on the Bosnian side, and Bosnians fighting on the Serb side. Contradictions and ironies abound, and thus to categorize the fighting in the ex-Yugoslavia as a tribal war is to dehumanize individuals. Moreover, given the legacy of the Holocaust, the West has a particular responsibility to prevent another genocide in Europe. Otherwise, what were World War II and the Cold War really about?

Obviously, if you look closely at Bosnia—as well as the Caucasus, Rwanda and other places—you will find that there is a lot more going on than just ethnic disputes. But that does not mean that the ethnic nature of those wars should be minimized. Every war is full of myth-breaking details.

The fact is, there was a great war in this decade in the former Yugoslavia, and it was fought overwhelmingly along ethnic lines—lines that have a long and rich history. Of course, the war could have been short-circuited more quickly had the United States acted more decisively. But one of the reasons why it didn’t—and still doesn’t in Kosovo—is that neither the Clinton administration nor the intellectual community has articulated well a crystalline and naked national interest that the millions of ordinary Americans can immediately grasp—people like my cab driver who don’t concern themselves with hair-splitting foreign policy discussions.

The history of U.S. foreign policy on this point is undeniable: Moral arguments will sometimes be enough to get troops abroad, but as soon as they start taking casualties, an amoral reason of self-interest is required to keep them in place. Look at Somalia: Most of the public supported the U.S. intervention to feed starving people there, but wanted the troops home as soon as soldiers started to lose their lives, because no clear national interest had been established.

Greece is the most misunderstood Balkan country. The West demands that Greece behave exactly like the other members of the alliance because it is middle class and a member of NATO. But it can’t, because it is in the Balkans and must adjust its foreign policy relative to its geographical position. Greeks know that they are fated to live next door to the Serbs long after any NATO troops leave.

Croatia and Serbia will always seek to advance the interests of their ethnic compatriots in Bosnia, at the expense of each other and of the Bosnian Muslims, no matter who is in charge, democrat or autocrat.

After the NATO air war against Serbia in 1999, in which Romania and Bulgaria showed themselves to be loyal allies of the West, providing military bases and rights to fly over their territory, hopes ran high in those countries that generous aid would be forthcoming. People there say they have been bitterly disappointed.

In Abroad: British Literary Traveling Between the Wars, the American scholar Paul Fussell writes that “the secret of the travel book” is “to make essayistic points seem to emerge empirically from material data intimately experienced.” In other words, at its very best, travel writing should be a technique to explore history, art, and politics in the liveliest fashion possible. Mary McCarthy’s The Stones of Florence and Dame Rebecca West’s Black Lamb and Grey Falcon are the best examples of this that I can think of.

“In Bulgaria and in Greece, in Yugoslavia, in all the countries of Europe which have lived under Turkish rule it is the same,” lamented the incarcerated Madame Deltchev, the victim of a Stalinist purge in Eric Ambler’s Judgement on Deltchev. “Then, our people lived behind their walls in small worlds of illusion … they painted the walls with scenes of national life.… Now that we are again inside our walls, the habits

Among the old photographs I looked at was one of the Habsburg Archduke, Franz Ferdinand, on military maneuvers outside Sarajevo, June 27, 1914, the day before he was assassinated—the crime that ignited World War I.

The Nazi occupation detonated these tensions. In primitive ferocity—if not in sheer numbers—the massacre in Catholic Croatia and neighboring Bosnia-Hercegovina of Orthodox Serbs was as bad as anything in German-occupied Europe. Forty-five years of systematized poverty under Tito’s Communists kept the wounds fresh.

I immediately grasped that the counterrevolution in Eastern Europe included Yugoslavia, too. But because the pressure of discontent was being released horizontally, in the form of one group against another, rather than vertically against the Communist powers in Belgrade, the revolutionary path in Yugoslavia was at first more tortuous and, therefore, more disguised. That was why the outside world did not take notice until 1991, when fighting started. It took

Here, she implied, the battle between Communism and capitalism is merely one dimension of a struggle that pits Catholicism against Orthodoxy, Rome against Constantinople, the legacy of Habsburg Austria-Hungary against that of Ottoman Turkey—in other words, West against East, the ultimate historical and cultural conflict.

The change proceeded under the dynamic influence of the archbishop-coadjutor, Alojzije Stepinac, who before the end of the year would assume the full title of Archbishop of Zagreb.

According to Stepinac’s own diary, he believed that Catholic ideals of purity should extend to Orthodox Serbia too. “If there were more freedom … Serbia would be Catholic in twenty years,” wrote Stepinac. His dogmatism caused him to think of the Orthodox as apostates. “The most ideal thing would be for the Serbs to return to the faith of their fathers; that is, to bow the head before Christ’s representative, the Holy Father. Then we could at last breathe in this part of Europe, for Byzantinism has played a frightful role … in connection with the Turks.” When Stepinac “was later during World War II faced with the fruits in practice of these ideas, he was horrified,” observed Stella Alexander, in a detailed and compassionate account of Stepinac’s career, The Triple Myth: A Life of Archbishop Alojzije Stepinac.

The official then told me of how Catholic priests, under the direction of Stepinac, officiated at forced mass conversions of Orthodox Serbs minutes before their execution by the Croatian Ustashe

Sulzberger recalled: “Orthodox Serbs of all political shades came up to me and growled: ‘Stepinac should have been hanged. It was he who condoned the murder of thousands of the Orthodox.’… When I got back to Zagreb, two men rushed up to me in the street and asked: ‘Are you the American journalist? Did you see the Archbishop (who was in a Communist jail at the time)?’ ‘Ah, he is a fine man, a saint. Tell the American people he is our hero.’” And when I returned to Zagreb five years later, at the end of 1989, the guilt or innocence of Stepinac was still The Story.

In Zagreb, I learned that the struggle for bare survival leaves little room for renewal or for creation. While Ukrainians and others openly apologized for their actions against Jews during the Holocaust, Croatian groups only issued denials. The statistics on mass murder in Croatia were exaggerated, I was told. Weren’t the Serbs also guilty of atrocities in World War II? And weren’t the remaining Jews in Croatia being treated well? Undoubtedly, these arguments had a certain validity.

Why did the Ukrainians act one way and the Croats another? Because the Ukrainians, in 1991 and 1992, were not having their cities bombed and their people brutalized in an unprovoked war of aggression. The war in Yugoslavia—the struggle for survival—has postponed the self-examination of Holocaust history in Croatia. But come it must.

But Bosnia was always light-years removed from Zagreb. Zagreb is an urbane, ethnically uniform community on the plain, while Bosnia is a morass of ethnically mixed villages in the mountains. Bosnia is rural, isolated, and full of suspicions and hatreds to a degree that the sophisticated Croats of Zagreb could barely imagine. Bosnia represents an intensification and a complication of the Serb-Croat dispute.

The fact that the most horrifying violence—during both World War II and the 1990s—occurred in Bosnia was no accident. In late 1991, a time when fighting raged in Croatia while Bosnia remained strangely quiet, Croats and Serbs alike had no illusion about the tragedy that lay ahead. Why was there no fighting in Bosnia? went the joke. Because Bosnia has advanced directly to the finals.

“The Serbs and the Croats were, as regards race and language, originally one people, the two names having merely geographical signification,” writes the British expert Nevill Forbes in a classic 1915 study of the Balkans. Were it not originally for religion, there would be little basis for Serb-Croat enmity.

Religion in this case is no mean thing. Because Catholicism arose in the West and Orthodoxy in the East, the difference between them is greater than that between, say, Catholicism and Protestantism, or even Catholicism and Judaism (which, on account of the Diaspora, also developed in the West). While Western religions emphasize ideas and deeds, Eastern religions emphasize beauty and magic. The Eastern church service is almost a physical re-creation of heaven on earth. Even Catholicism, the most baroque of western religions, is, by the standards of Eastern Orthodoxy, austere and intellectual. Catholic monks (Franciscans, Jesuits, and so on) live industriously, participating in such worldly endeavors as teaching, writing, and community work. In contrast, Orthodox monks tend to be contemplatives, for whom work is almost a distraction, since it keeps them from the worship of heavenly beauty.

That was the refrain you heard throughout the Balkans, in Dame Rebecca’s day and in mine. Dame Rebecca writes: “The Turks ruined the Balkans, with a ruin so great that it has not yet been repaired.… There is a lot of emotion loose about the Balkans which has lost its legitimate employment now that the Turks have been expelled.” If like the Russian Nobel laureate Joseph Brodsky you view the Communist Empire as the twentieth-century equivalent of the Ottoman Turkish Empire, with the historical compass line of decrepit, Eastern despotism traveling north from Istanbul (formerly Constantinople) to Moscow—from the Sultan’s Topkapi Palace to the Kremlin—then Dame Rebecca had already capsulized the situation in Serbia, in the rest of former Yugoslavia, and in the other Balkan states for the 1990s. Now that Communism has fallen and the Soviets have been expelled, there is a lot of emotion loose about the Balkans which has lost its legitimate employment.

Out there is what Nevill Forbes and John Reed in 1915, what Dame Rebecca in 1937, and what Mother Tatiana now called “Old Serbia”: the “Judea and Samaria” of the Serbian national consciousness, the place where it all happened, where the great Nemanjic kingdom was born, grew to greatness, and was destroyed. In recent decades, however, this hallowed ground has been demographically reclaimed, not by the Turks, but by their historical appendants, the Muslim Albanians. Thus this region is no longer referred to as Old Serbia, but as “Kossovo.” Yet it was “the Turk” that Mother Tatiana still meant to hate. Without the cultural and economic limbo of half a millennium of Turkish rule, Communism might not have been established here so easily, and the Albanians might never have been converted to Islam and settled in such large numbers as they were in old Serbia.

To Mother Tatiana and to many other Serbs, Tito’s Yugoslavia signified—like the former Turkish Empire—just another anti-Serbian plot. This was because Yugoslav nationalism, as Tito (a half-Croat, half-Slovene) defined it, meant undercutting the power of the numerically dominant Serbs in order to placate other groups, particularly the Croats and the Albanians.

In 1987, an ambitious Serbian Communist party leader, Slobodan Milosevic, came to this area on the June 28 anniversary of Lazar’s defeat. He pointed his finger in the distance—at what Mother Tatiana had labeled out there—and, as legend now has it, pledged: “They’ll never do this to you again. Never again will anyone defeat you.”

The only Eastern European Communist leader in the late 1980s who managed to save himself and his party from collapse did so by making a direct appeal to racial hatred.

When Turkish rule in Albania finally began to collapse during the First Balkan War of 1912, the Albanians once again found themselves alone against larger enemies. Serbs, Greeks, and Bulgarians all invaded Albania, claiming to liberate it but in fact intending to carve it up into various spheres of influence. In 1913, Great Power intercession resulted in the creation of an independent Albanian state, minus the Muslim province of Kossovo, which the Serbs grabbed.

And to compensate Habsburg Austria-Hungary for this new provocation, Bismarck arranged for Bosnia, the province next door to Serbia, with a Serbian population that also wanted independence, to be transferred from Ottoman rule to Habsburg rule—the immediate cause of World War I. Great Britain, for its part, received from the Turks the island of Cyprus.

“Do not tell me about Macedonia,” the Bulgarian diplomat in Athens had raged. “There is no Macedonia. It is western Bulgaria. The language is 80 percent Bulgarian. But you don’t understand; you have no grasp of our problems.… Gotse Delchev was a Bulgarian.

In the Balkans, people spoke more honestly than in the Middle East, and therefore more brutally. Dr. Ivanovski went on: “The Bulgarians, you know, have specialized teams who invent books about Gotse Delchev. They bribe foreign authors with cash and give them professorships in order to put their names on the covers of these books. I know that the Bulgarians are now buying up advertising space in India to propagandize about Macedonia and Gotse Delchev. “How could Gotse Delchev be Bulgarian?

Throughout Macedonia it was the same. The two-month uprising cost the lives of 4,694 civilians and 994 IMRO guerrillas. Estimates put the total number of women and girls raped by the Turks at over 3,000.4 In northwestern Macedonia, fifty Turkish soldiers raped a young girl before finally killing her. Turkish soldiers cut off another girl’s hand in order to take her bracelets. A correspondent for the London Daily News at the scene, A. G. Hales, wrote in the October 21, 1903, edition: “I will try and tell this story coldly, calmly, dispassionately … one must tone the horrors down, for in their nakedness they are unprintable.…” Public protests ensued against the Turkish Sultanate throughout Great Britain and the West. Pressure from British Prime Minister Arthur James Balfour, Russian Czar Nicholas II, and Habsburg Emperor Franz Joseph resulted in the entrance of an international peacekeeping force into Macedonia in 1904. Not by accident, the Hurriyet (“Young Turk” Revolution), which toppled the Ottoman Sultanate, originated in the Macedonian port of Salonika, where a young Turkish major, Enver (soon to be called Enver Pasha), stood on the balcony of the Olympos Palace Hotel on July 23, 1908, and acknowledged the cheers of a multiethnic crowd acclaiming “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity, Justice.” Mustapha Kemal “Ataturk,” the future father of modern Turkey, was also a Macedonian, born

Put another way, Bulgarian-financed guerrillas in Macedonia had triggered a revolution among young Turkish officers stationed there, which then fanned throughout the Ottoman Empire; this development, in turn, encouraged Austria-Hungary to annex Bosnia, inflicting on its Serbian population a tyranny so great that a Bosnian Serb would later assassinate the Habsburg Archduke and ignite World War I.

The increasingly authoritarian nature of the Young Turk regime culminated with their 1915 mass murder of an estimated 1.5 million Armenians, the century’s first holocaust. This government-orchestrated genocidal campaign was perpetrated because the Armenians, unlike their fellow Eastern Christians in the Balkan peninsula, demographically threatened the Muslim Turks in their historic heartland, central Anatolia. The Empire—any empire—a young and skeptical Kemal Ataturk foresaw wisely, had no future in this new age. The development of the Young Turks into more brutal and efficient killers than the Sultan had been, together with the unwillingness of the other Great Powers to interfere, prompted Bulgaria, Serbia, and Greece to accomplish what no one had thought possible: they submerged their differences and formed an alliance.

The First Balkan War ended in December 1912 with the dissolution of Turkey in Europe.

Meanwhile, in Bulgaria, the government and the people smoldered. At 1 A.M. on June 30, 1913, without any warning or declaration of war, the Bulgarian army crossed the Bregalnitsa, a Vardar tributary, and attacked the Serbian forces stationed on the other side. The Second Balkan War had begun. The battle lasted several days. The Serbs recovered the advantage and were soon helped by Greek reinforcements. Then the Romanians joined the Serb-Greek alliance and invaded Bulgaria from the north, in a campaign that saw more men die of cholera than of bullet wounds. At the August peace conference in the Romanian capital of Bucharest, Bulgaria lost everything: its outlet on the Aegean Sea, its gains in Thrace from the First Balkan War, and every square inch of Macedonia. This disaster was to have grave consequences for world history.

In the fall of 1915, Bulgaria entered World War I on the side of the Central Powers (Germany and Austria-Hungary) in order to regain Macedonian territory from Serbia, which had aligned itself with the Triple Entente (czarist Russia, Great Britain, and France).

“Two thirds of Macedonia is under foreign occupation and still to be liberated,” explained another local poet, Ante Popovski, whom I met on the same brandy-filled morning. He chain-smoked and scribbled constantly in a notebook. His face was like a clenched fist. “The rest of Europe in 1989 achieved their national rights, but not yet the Macedonians in Greece and Bulgaria, who are under occupation.”

The upshot of this mess is that the Balkans have, in the 1990s, reverted to the same system of alliances that existed in 1913, at the time of the Second Balkan War: Greece, Serbia, and Romania versus Bulgaria and the Slavs of Macedonia.

But Djilas’s mind was already in the 1990s: “Milosevic’s authoritarianism in Serbia is provoking real separation. Remember what Hegel said, that history repeats itself as tragedy and farce. What I mean to say is that when Yugoslavia disintegrates this time around, the outside world will not intervene as it did in 1914.… Yugoslavia is the laboratory of all Communism. Its disintegration will foretell the disintegration in the Soviet Union. We are farther along than the Soviets.”

Romania, too, was always alone, always surrounded by enemies who wanted pieces of her.

“It is all the fault of Roosevelt. Everything here,” waving his hand. “He sold Romania out at Yalta. Otherwise Romania would be like France today.”

“Roosevelt was near death’s door at Yalta; he died a few weeks later,” I started to explain. “The agreement he negotiated with Stalin called for free elections in Eastern Europe. It wasn’t his fault that the Red Army’s presence in these countries made the agreement unenforceable. Blame Stalin, blame Hitler for beginning the war in the first place. But don’t blame Roosevelt.”

“When the Romanian army was forced to withdraw from Bessarabia near the end of World War II, my other grandmother had forty-eight hours to leave her house, her parents and her brother, and everything she owned. Later, she learned that the Russians had executed her father and her brother. She blamed the Americans for this, for not helping Romania against the Russians.

Hungary, like Romania, was governed by a Hitler-allied fascist dictatorship during World War II. The cruelties it perpetrated in Transylvania against the local Orthodox population (and particularly against the Jews), nearly equaled the barbarity exhibited by the Romanians elsewhere.

We have an expression in Romania, ‘Hirtia suporta maimult ca betonul—Paper is harder than stone.’ It is only with pencil and paper that you can really torture and murder on a mass scale. “Stalin at least had some education.”

Romania’s loss would be Germany’s gain: another case of the rich getting richer and the poor poorer. The Saxons, along with the Jews, were the only people in Romania with a tradition of bourgeois values: standing, economically, between the wealthy nobles and the mass of downtrodden peasants. But just as Romania was beginning to emerge from Communism, just as it desperately needed the Saxons to act as a motor driving Romanian society in the direction of middle-class capitalism, the last Saxons of working age were leaving for Germany. And not only Romanian Saxons were leaving for Germany. So were millions of other ethnic Germans—from Silesia and Pomerania in western Poland, and from East Prussia, the Volga region, and Soviet Central Asia. All were like Lorenz, willing to work, work, work: to take the jobs that prosperous Germans didn’t want, and to make themselves middle class in the process.

Germany was going to be a much more powerful nation than even the addition of East Germany would have indicated. The era of Soviet domination in the Balkans was about to give way to an era of German domination. German economic imperialism, I realized, offered the most practical and efficient means of bringing free enterprise, democracy, and the other enlightened traditions of the West to Romania.

While extramarital affairs in the West were mainly a result of middle-class boredom, here I felt they served deeper needs. With politics and public life so circumscribed, there was a huge well of authentic emotion that even the most ideal of marriages could never consume. And perhaps because you could never escape from the cold, even when indoors, a warm body at night was not enough: you needed one during the day too.

“Slaves you call us. Yes, there is that silly word you in the West use—a satellite, as though we Bulgarians were going around in space. Nonsense. You know nothing about what the Turks did to us, what it was like under the yoke of the sultans. The Russians liberated us from that, but we are proud. We fought the Russians in World War I. Okay, so now we are weak and surrounded by enemies. So we use the Russians as a protector while we deal”—Guillermo rubbed his thumb against the back of his fingers—“against the Turks, the Greeks, and the others. The Russians give us great leeway, my dear, in our dealings with the Turks, the Greeks, the Serbs. How can you say we have no freedom? The Russians give us cheap oil and other raw materials. We bleed the Russians.

A Russian army swept through Bulgaria in 1877 and 1878, liberating Bulgaria from Ottoman subjugation in order to create a pro-Russian, Bulgarian buffer state against the Turks. Although the 1878 Treaty of Berlin forced newly independent Bulgaria to cede Thrace and Macedonia back to Turkey—triggering a renewed outbreak of guerrilla war—Bulgarian gratitude to the Russians never entirely dissipated. The Russian liberation was one of the few happy moments in Bulgaria’s history since the Middle Ages.

In terms of military occupation and loss of land, Soviet domination cost the Bulgarians little. Because their country was not contiguous to the Soviet Union, the Soviets had no territorial claims to make—unlike in the cases of Romania, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Poland, whom the Soviets forced to give up territory as the Soviet border moved westward after World War II. Located farthest away from the line of confrontation between East and West in Central Europe, Bulgaria was also the least strategically important of all the Warsaw Pact states. Thus, when local Communists consolidated control under the leadership of the Moscow-trained Dimitrov in December 1947, the Soviet army withdrew from Bulgaria, never to return except for yearly maneuvers.

I had returned to Sofia on account of disturbing reports. The Communist authorities were forcing 900,000 people, 10 percent of the country’s population, to change their names. The people affected were all ethnic Turks, the human residue of Turkey’s 500-year-long subjugation of Bulgaria. Every “Mehmet” was made to become a “Mikhail,” and so on.

Just as Serbia, Albania, Romania, and Bulgaria brutally smashed through the undergrowth of Ottoman tyranny and diversity to erect ethnically uniform states, so did Greece. And as the memory of the Albanians was erased by the Serbs, as the memory of Greek Northern Epirus was erased by the Albanians, that of the Hungarians by the Romanians, and that of the Turks by the Bulgarians, so too was the memory of Salonika’s Jews and other ethnic groups erased by the Greeks. Greece is part of the Balkan pattern, particularly in this city, the former capital of Ottoman-era Macedonia.

As the 1990s began, Greece was increasingly making the news in connection with border disputes in Macedonia and southern Albania.

The first time I arrived in Greece was by train from Yugoslavia. The second time was from Bulgaria, also by train. A third time was by bus from Albania. Each time, upon crossing the border into Greece, I became immediately conscious of a continuity: mountain ranges, folk costumes, musical rhythms, races, and religions, all of which were deeply interwoven with those of the lands I had just come from. And just as everywhere else in the Balkans, where races and cultures collided and where the settlement pattern of national groups did not always conform with national boundaries, this intermingling was hotly denied.

That is why, when I arrived in Greece from Bulgaria in 1990, I did not think of myself as having left the Balkans, but as having entered the place that best summed up and explained the Balkans. The icon was a Greek invention. The Greek Orthodox Church was the mother of all Eastern Orthodox churches. The Byzantine Empire was essentially a Greek empire. The Ottoman Turks ruled through Greeks—from the wealthy, Phanar (“Lighthouse”) district of Constantinople—who were often the diplomats and local governors throughout the European part of the Turkish empire. Constantinople was a Greek word for an historically Greek city.

Until 1918, when the Ottoman Empire collapsed, Turkish was an important foreign language for diplomats and journalists. Then, in a breathtakingly short period of time, it became just another obscure tongue. As the world moved into an age in which politics was becoming submerged beneath economics and trade competition, would Russian join Turkish in obscurity?

The Bosnian Muslim dead were most all soldiers, and the Bosnian Muslims also fought with Croats – the Croat-Muslim war – which lasted from October 1992 through February 1994. The west forced them into a peace deal, as the west wanted them united, again, to attack Serbs.

The Bosnian Muslims had the largest army – 200,000 men – which was several times larger than the Bosnian Serb forces, only around 40,000.

Plus Croatia sent in 40,000.

It was an open secret that Croatia had its officers and soldiers there throughout the entire war.

They were not threatened with sanctions nor bombings and the western governments and officials were quiet about it, even though they knew it.

Sarajevo is now almost pure Muslim – its the Serbian population which dropped by 160,000.

They cleansed the Sarajevo Serb civilians, in the part of Sarajevo the controlled, and the city was DIVIDED with the front lines snaking through the middle, including near to the infamous Holiday Inn where foreign reporters stayed.

UN officers have testified and UN reports documented that Muslim snipers in Sarajevo did shoot at civilians and the UN personnel there. Also, a UN officer testified that their snipers/forces used several buildings in Sniper’s Ally.

The fact that the Bosnian Muslims had the largest amount of snipers, who were the most active, in Sarajevo, yet the mainstream media automatically blamed Serbs gave them a blank check to snipe civilians and have the Serbs be blamed and demonized.

The Bosnian Muslims did continually stage attacks – including ones were they pre-set up cameras – to make propaganda against the Serbs.

French UN officers caught Bosnian Muslim snipers filming their shooting at Sarajevo civilians in which a teen-aged boy got injured. No doubt they were filming this for the news to blame “Serb snipers”.

Canadian soldier, James R. Davis, wrote in his book that the Bosnian Muslims mortared their own, including children for PR (political reasons) purposes.

He said they were “animals” who “just didn’t care”.

There were thousands of Sarajevo Serb CIVILIANS killed by the Bosniaks in Sarajevo.

Sarajevo Serbs were being decapitated and thrown down the Kazani gorge by the commander of the Bosnian Muslim 10th Mountain Brigade.

Bosnian Muslims put the civilian Serbs in grain silo concentration camps, such as the Silo at Tarcin – hundreds of civilian Serbs there, and also kept them in tunnels. The UN knew about this, but did nothing.

The UN food was going to the Bosnian Muslim army and the black marketers wherever the UN was stationed – and it was in Sarajevo for the entire war and even before (they arrived in February 1992).

The food was regularly being trucked in, but the Bosnian Muslim government was only distributing 40% of the food, according to UN documents. The UN believed it was stockpiling the rest.

Of that 40%, it was going to the army – which was never deprived – or the black market.

The Bosnian Muslim government, led by UNELECTED Bosnian president Alija Izetbegovic, was purposely withholding the food from the civilians to cause deprivations and suffering of the people in order to blame the Serbs.

Just like their staged mortar attacks, constant sniping of both Serbs and civilians within their own lines, and also interfering with the utilities more than the war itself.

They were and are professional victims and huge propagandistic liars.

Sarajevo Shuns Recognition of Bosniak War Crimes

“Another case of beheadings of Serbs is documented to have happened on Kazani, on Trebević mountain above Sarajevo. Mostly Serb civilians were killed by beheading, and later on thrown in the Kazani pit. These actions were performed by several soldiers of the 10th mountain brigade under the command of Mušan Topalović – Caco.”

http://www.balkaninsight.com/en/article/sarajevo-shuns-recognition-of-bosniak-war-crimes

At the time almost 1,000 ethnic Serbs and Croats were held in three camps and detention facilities in the area, notably in Silos camp in Tarcin, the prosecutors said.

The detainees were tortured, beaten and submitted to forced labour.

According to police sources, several dozen detainees were killed in the three facilities.

http://www.focus-fen.net/index.php?id=n267515

Secret Bosnian Muslim sniper group targeted own people, accusing Serbs of wanton killing, testifies Muslim chief. http://www.nezavisne.com/novosti/bih/Garaplija-Snajpersko-djelovanje-Seva-pripisano-Srbima-178992.html

The Muslim Larks (aka “Seve”) were just one of several Muslim paramilitaries that went about terrorizing Serbs, Croats, and in some cases their own Muslims. They operated primarily in Sarajevo. Other examples are the Patriotic League (“Patriotska Liga”), Green Berets (“Zelene Beretke”), Mosque Doves (“Dzamijski Golubovi”), Black Swans (“Crni Labudovi”), etc.

from “Dvorak Fan” on Amazon.com

http://www.amazon.com/review/R17ROGWU8ACYG0/ref=cm_cr_pr_cmt?ie=UTF8&ASIN=0760330034&linkCode=&nodeID=&tag=#wasThisHelpful

Muslim Hazim Delic (Celebici camp) boasted in front of the inmates that he had raped 60-120 Serbian women. http://www.serbianna.com/columns/savich/047.shtml

Bosnian Army Troops ‘Systematically Executed Croat Villagers http://www.balkaninsight.com/en/article/ordering-executions-of-bosnia-villagers

Former Al Qaeda warrior in Bosnia: “We were torturing Serbs in concentration camps, hammered them alive, drove rusty nails through their genitals” http://chasvoice.blogspot.com/2013/12/former-al-qaeda-warrior-in-bosnia-we.html

Three persons indicted for killing 90 Serbs in Trnovo [Bosnia] http://www.tanjug.rs/news/135662/three-persons-indicted-for-killing-90-serbs-in-trnovo.htm

More than 300 foreign fighters (Mujahideen) buried in Bosnia http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-33345618

Feb 2015 Six Bosnian Immigrants Living in U.S. Assisted ISIS with Money and Weapons, Indictiment Shows

http://www.hngn.com/articles/67568/20150207/six-bosnian-immigrants-living-u-s-assisted-isis-money-weapons.htm

Fresh with the perspective of the Balkan civil war in mind, did you return from your trip to the Balkans with any change in perspective or concern as to how divisive issues – for example, racial divisions – are covered by the media in America?

Hi James, Not any precise new perspective on U.S. media coverage of race relations here. With respect to U.S., my perspective is more about Native Americans and the Mexicans and our own historical past…

As Simon and Garfunkel said in “Scarborough Fair”:

Generals order their soldiers to kill and to fight for a cause they’ve long ago forgotten.