While traveling to Africa a few weeks ago, I read Dark Star Safari: Overland from Cairo to Cape Town by Paul Theroux. Theroux is probably America’s most famous travel writer yet I had not read any of his books until now. Dark Star Safari was excellent and I recommend it for anyone taking a trip to the giant continent. It’s the travelogue of his overland journey — car, bus, animal — from the northern tip of Africa to the bottom.

While traveling to Africa a few weeks ago, I read Dark Star Safari: Overland from Cairo to Cape Town by Paul Theroux. Theroux is probably America’s most famous travel writer yet I had not read any of his books until now. Dark Star Safari was excellent and I recommend it for anyone taking a trip to the giant continent. It’s the travelogue of his overland journey — car, bus, animal — from the northern tip of Africa to the bottom.

He does it on the cheap: he reports from wretched-smelling train cars, rat infested hotel rooms, and dusty, poor villages where clean water is nowhere to be found. I read portions of the book in comfortable hotels or cars in Tanzania, often whizzing by the abject poverty. Theroux doesn’t make you feel great about that, but maybe that’s a good thing.

Theroux lived in Malawi back in the day and he doesn’t mince words when he returns and finds the poverty just as bad, the aid programs just as ineffective. Foreign aid diehards should be prepared for tough medicine from Theroux who at one point says that the only people who can fix Africa’s problems are Africans themselves.

The writing is lovely. His descriptions vivid. Below are my Kindle highlights. (And here is my post from 2009 about Theroux road trip in America and my own road trip impressions.)

Some countries are perfect for tourists. Italy is. So are Mexico and Spain. Turkey, too. Egypt, of course. Pretty big. Not too dirty. Nice food. Courteous people. Sunshine. Lots of masterpieces. Ruins all over the place. Names that ring a bell. Long, vague history. The guide says “papyrus” or “hieroglyphic” or “Tutankhamen” or “one of the Ptolemys,” and you say “Yup.”

One of the problems I had with travel in general was the ease and speed with which a person could be transported from the familiar to the strange, the moon shot whereby the New York office worker, say, is insinuated overnight into the middle of Africa to gape at gorillas. That was just a way of feeling foreign. The other way, going slowly, crossing national frontiers, scuttling past razor wire with my bag and my passport, was the best way of being reminded that there was a relationship between Here and There, and that a travel narrative was the story of There and Back.

Now a complex infrastructure was devoted to what had become ineradicable miseries: famine, displacement, poverty, illiteracy, AIDS, the ravages of war. Name an African problem and an agency or a charity existed to deal with it. But that did not mean a solution was produced. Charities and aid programs seemed to turn African problems into permanent conditions that were bigger and messier.

The greatest part of my satisfaction was animal pleasure: the remoteness of the site, the grandeur of the surrounding mesalike mountains and rock cliffs, the sunlight and scrub, the pale camels in the distance, the big sky, the utter emptiness and silence, for round the decay of these colossal wrecks the lone and level sands stretched far away.

The whites, teachers, diplomats, and agents of virtue I met at dinner parties had pretty much the same things on their minds as their counterparts had in the 1960s. They discussed relief projects and scholarships and agricultural schemes, refugee camps, emergency food programs, technical assistance. They were newcomers. They did not realize that for forty years people had been saying the same things, and the result after four decades was a lower standard of living, a higher rate of illiteracy, overpopulation, and much more disease. Foreigners working for development agencies did not stay long, so they never discovered the full extent of their failure. Africans saw them come and go, which is why Africans were so fatalistic. Maybe no answer, as my friend said with a rueful smile.

Urban life is nasty all over the world, but it is nastiest in Africa—better a year in Tabora than a day in Nairobi. None of the African cities I had so far seen, from Cairo southward, seemed fit for human habitation, though there was never a shortage of foreigners to sing the praises of these snake pits—how you could use cell phones, send faxes, log onto the Internet, buy pizzas, and call home—naming the very things I wanted to avoid.

That was my Malawi epiphany. Only Africans were capable of making a difference in Africa. Everyone else, donors and volunteers and bankers, however idealistic, were simply agents of subversion.

No objects I had seen in any African museum (Nairobi, Kampala, Dar es Salaam, and Harare) could compare with the African objects in the museums in Berlin, Paris, or London. Of course, much of that stuff had been looted or snatched from browbeaten chiefs

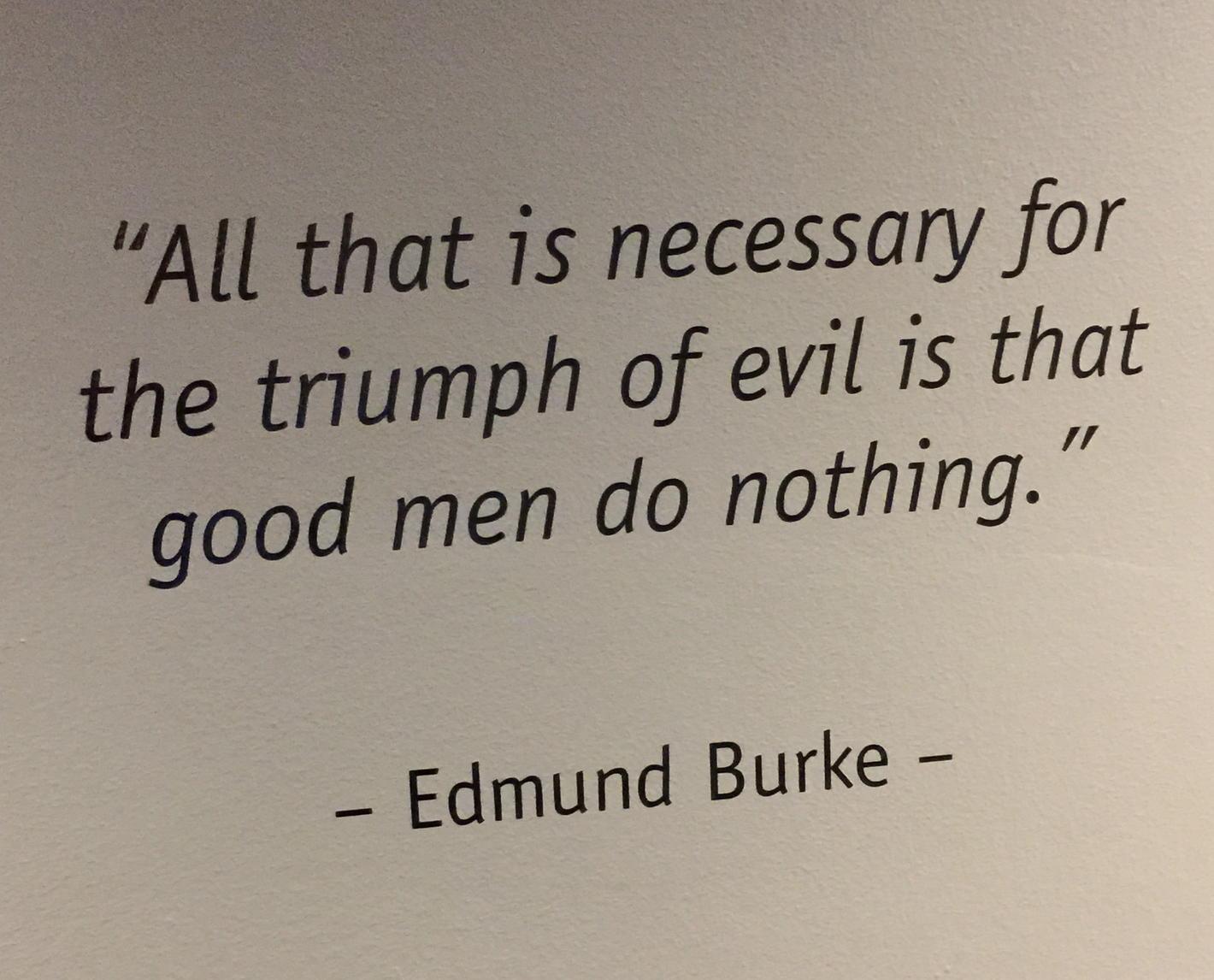

ers and executed 8,000 men and boys in 48 hours. The photo embedded to the right hangs on the wall as you exit the museum. You can’t help but reflect on the costs and benefits of humanitarian interventions.

ers and executed 8,000 men and boys in 48 hours. The photo embedded to the right hangs on the wall as you exit the museum. You can’t help but reflect on the costs and benefits of humanitarian interventions.